This is a compound reflection on both Mozilla Hubs and A-Frame. Together, this platform and framework were the key open-source development environments for VR online during the period of study. I wrote this reflection while Mozilla Hubs was still active and am updating now at the end of the research cycle.

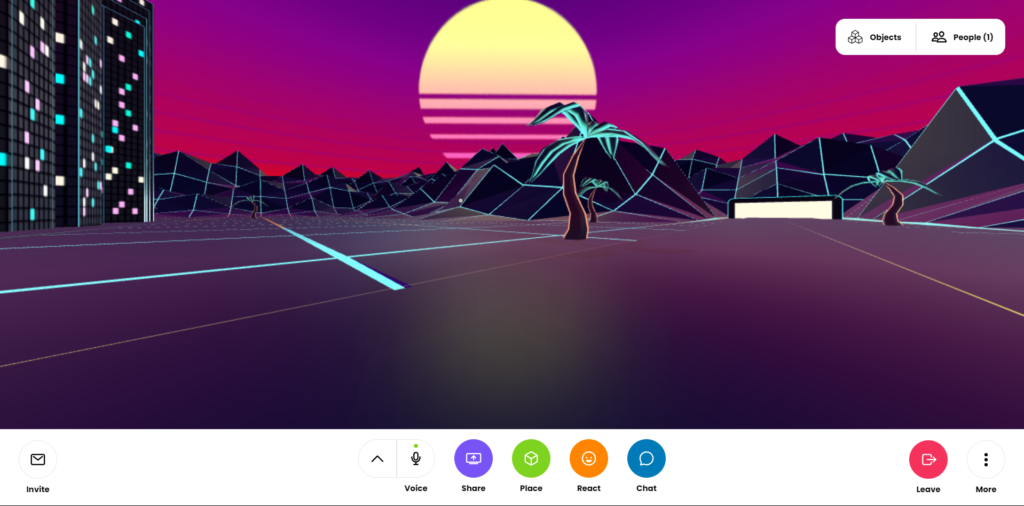

In this reflection, I consider three elements. The underlying core for Mozilla Hubs is all open source, built on HTML and JavaScript using A-Frame, so it’s accessible for coders working in (relatively) simple languages. Hubs was (is) a platform that enabled users to access that framework through a drag-and-drop interface and rapidly develop spatial environments that could be accessed in VR and host multiple users simultaneously. Spaces could be augmented using media and 3D models, and 360-degree images. It was the full package, although a little bit clunky and cumbersome to use. It was entirely free initially, although restrictions were applied as the platform developed.

The third element, after the underlying code and framework, and the platform, was a development environment called Spoke. Spoke was notable because it was professional-level software that enabled users to quickly prototype and create VR spaces in a desktop-style application; no coding required.

Feelings:

As of now, in 2024, Mozilla Hubs is being sunsetted. The intention is that it will be transferred to a community organisation, the Hubs Foundation. There is precedence for this. Netscape Navigator was originally a commercial web browser competing with Internet Explorer. When that technology was closed down, it was transferred into the open-source community, and a foundation was established for continuous development. That foundation was the Mozilla Foundation, and the browser became Firefox. So, it’s interesting to see the same model being applied here, and it means that there is some hope in the future that continual development on an open-source VR development platform will take place.

Update: as of October 2024, the foundation has enabled developers to set up their local instances of Hub, which I’ll be exploring.

Evaluation:

The web was built on open-source software and protocols and has increasingly become more commercial in the 30 years it’s been established. However, HTML, HTTP, Cascading Style Sheets, JavaScript, JPEG, GIF, all these foundational elements of the web were developed by open-source communities, and VR will only thrive if we have the same open-source approach to its development. Mozilla Hubs was clunky, unfinished, and ugly in places. Still, it also had a lot of promise and all of the significant features one would need to develop interactive VR journalism if the right tools to harness the underlying framework and platform were in place. Spoke was not that tool. Spoke was a tool for creating spatial environments with limited scripting. Some of the available commercial tools, for example, Frame VR, now include AI generation of elements in the environment, non-player characters, and so on, which shows us where they could develop in future.

Application:

I used Mozilla Hubs to place 3D models that had been scanned photogrammetry easily. I was able to label them and place them within spaces very quickly using cross-platform 3D modelling formats. A workflow from mobile phone 3D model photogrammetry to Hubs to rapidly prototype an environment for telling stories is entirely plausible in the future.

Conclusions:

Mozilla Hubs and A-Frame are in a kind of limbo. The framework and approach are promising, but until an open-source or more accessible solution is made more widely available, it will remain there.