Blender is an open-source 3D modelling, animation, and design tool that is more powerful than any of the other programmes I reviewed during the study. It has been around for decades during which it evolved into a professional-quality package with many features and certainly more capabilities than I required.

At a basic level, Blender is an application for creating 3D models and has a robust toolset for doing this from scratch. Models can be created from primitives or drawn as coordinates and then extruded. Intersection and grouping tools can be used to amend and edit these models. Modern versions of Blender also include sculpting tools, making it an excellent platform for creating objects and assets.

To complement this, lighting and texture tools enable developers to create realistic surfaces, with different levels of reflectivity and tangibility. It is possible to build realistic organic or industrial models from scratch.

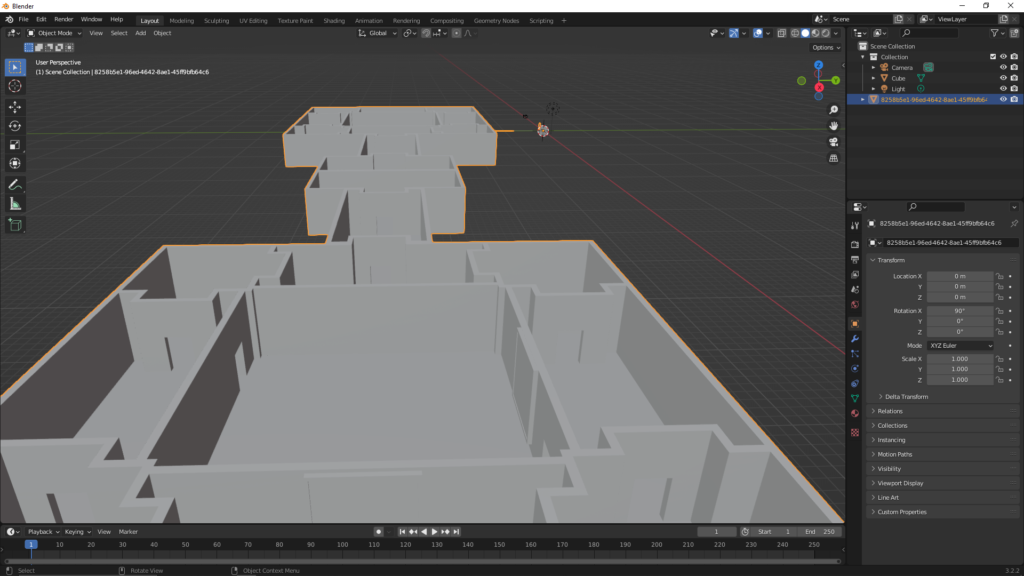

In addition, we can import existing 3D models into Blender in many formats, including photogrammetric scans. These can be edited in the same way, allowing us to refine models derived from real-world objects and spaces. These are all welcome features for an immersive journalism workflow.

However, Blender goes beyond even this, with built-in animation tools, keyframing, armature, and character creation capabilities. An application with this many features (and more) is every bit as complex as that makes it sound, with these features available in a number of tabbed workflows that amount to a suite of tools, rather than one focused programme.

Feelings

I may have shied away from Blender because of its overwhelming complexity. While the other tools I used during my projects and studies generally performed one function, Blender, although open-source, is professional-level quality 3D software for a variety of purposes. The prospect of learning its workflows is significant.

When I gravitated towards using it, it was for one-off specific jobs that I might not be able to perform in other software. For example, I found myself using it to clean up photogrammetric scans or to re-encode files for different platforms and formats. This is very much why the phrase “using a sledgehammer to crack a nut” was created. Blender is useful for creating professional-level, realistic 3D models, and my use of it made me realise that I was sacrificing professionalism and quality for speed.

With any project, there are a number of factors to consider. For immersive journalism, I prioritised rapid production workloads and low costs. I realised that my instinct to do this stemmed from a commercial imperative, with the assumption that creating functional immersive journalism would mean establishing an accessible workflow that organisations would accept as a reasonable risk. As a result, I sacrificed overall quality. This may have been an error, and it is something I will continue to investigate as I move into a new phase of research and begin to create volumetric immersive journalism as an output of the work. Blender may well be central to this next phase.

Evaluation

Blender’s toolset is easily on par with commercial software. In that sense, it is something of a hangover from the early open-source software movement, as it is entirely free and very powerful. It can be used to create objects or spaces and is optimised for CGI animation in particular.

However, I don’t think my decision to use SketchUp for the rapid production of architectural spaces was an incorrect call, as that is exactly what that software is for; much of immersive journalism production is the creation of spaces. Blender is arguably a tool that is better at creating objects (although it is good for spatial design too).

If there are any particular limitations, they are associated with interoperability with asset databases. The availability of 3D Warehouse for SketchUp was just as much a consideration as the ease of use of the software.

Application

Blender could easily be used for a variety of steps in the immersive journalism production workflow instead of or in addition to SketchUp. Its value as a tool for cleaning up photogrammetric scans alone assures this position, but this is coupled with its robust modelling capabilities, which might enable it to create “hybrid” spaces rapidly using photogrammetry, textures, and modelling. Add to this the advanced texturing, lighting, and rendering tools built in, and that makes the decision easier—as does the fact that it is free.

Conclusions

In the future, Blender may well replace SketchUp in my workflow, but to get there, I will need to improve my knowledge and use of it. One approach would be to take formal training in its use as a next step.