The gallery project is one that I revisited several times throughout the research. I first thought about creating a gallery while playing The Stanley Parable, a first-person explorer game that deconstructs and parodies first-person gaming. A secret area in the game is a gallery that lets players look at and explore design materials used in its creation. It is a significant space, relatively simple in design. During the same period, between 2016 and 2020, I was also engaged in a personal project developing a series of electronic computer-generated images. It was a natural extension of this project to create a virtual gallery space to exhibit them, which I did. I revisited this project often, particularly when using a new piece of software for the first time. I explored modular room-building techniques and virtual reality distribution platforms in different project iterations. In total, there were two significant iterations alongside some minor ones.

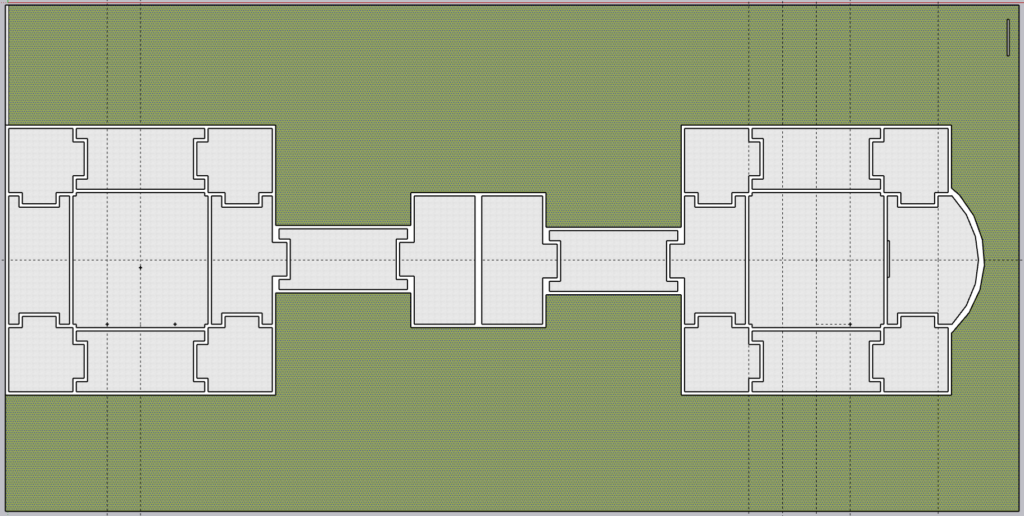

First, I created several gallery spaces in SketchUp and a series of tessellating room parts, making it easy to develop further galleries (like LEGO). I also built a similar gallery space in Unity using ProBuilder at first and later the integrated version of the same plugin. The second major iteration of the project was the creation of a gallery in Spatial.io. In this case, I used an off-the-shelf template rather than building my own space and populated it with images from my personal project. In the project’s first iteration, I concentrated on building methods, prototyping, and level building. In the second version of the project, I was more focused on rapidly creating and deploying a virtual reality environment.

Feelings

I had different feelings about various aspects of the project. The work I did in Unity was the most satisfying at the time, as I was creating space rather than recreating spaces, (which is what one would have to do when working on immersive journalism). I found it liberating to follow my imagination, and although I learned techniques and processes from this, there was also some satisfaction in unleashing that creativity. Similarly, in SketchUp, I found the initial iteration to be freeing and fun to create.

In the other project, I had no such reservations or boundaries, and combining the two would involve importing my models into Spatial to use instead. The template demonstrated that this rapid workflow was possible with features and functions built into the software platform, including shared telepresence.

Evaluation

During the initial research phase, I developed rapid room creation techniques using extrusion in SketchUp, which I could then mirror and apply in Unity. I also transferred the floor plan approach I designed in SketchUp and other modelling techniques. In some ways, the gallery spaces became some of the most complex spaces to build.

Application

Although this was the most creative of the projects, I was mindful that this wasn’t the main purpose of the exercise. I searched for and found maps of the National Gallery in London and created a model partly based on the layout of a single floor. This work was more meticulous and required measuring areas to ensure authenticity. As a proof of concept, it showed that interior design spaces are more complex to produce. Working on a plan brings its own constraints, as does the process of testing. I can see an approach that mixes the use of pre-fabricated parts with photogrammetry and more careful direct reproduction of real spaces to speed up production.

Conclusions

Spatial allows users to integrate Unity with the platform, and though I didn’t get to this stage, I can see a workflow between the two that would enable rapid deployment as a result of this specific work.